Frank Miller and the Antihero: Dark Noir Themes and Complex Characters

by Michael Flores

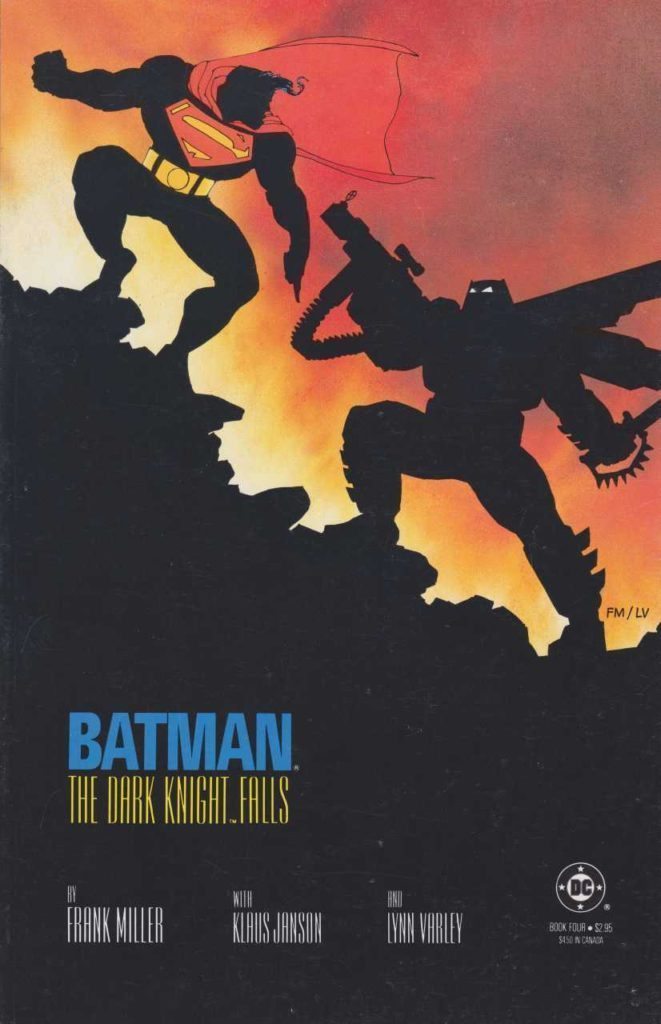

Frank Miller’s dark noir themes and his complex imperfect characterizations of his characters are vital elements that help bring to life the perfect antihero. Through realistic narratives, Miller manages to show the world from the perspective of his protagonists. Taking two notable antihero characters like Batman from Batman: Year One and Marv from Sin City: Vol 1 the reader can see sharply defined similarities and distinctions between the two. But the one element that keeps Batman and Marv synonymous is the very definition which makes them the perfect examples of antiheroism.

To understand the antihero, we must first define the meaning. According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the antihero is a central character in a story, movie, or drama who lacks conventional heroic attributes (“antihero”). The concept of a hero that lacks conventional qualities is not a new idea. The origins can be traced as far back as Greek Mythology, however several film movements of the early and late 20th century solidified its importance within pop culture. The first appearances of the antihero were deeply tied to the film genre known as film noir or rather “black film”, which span from the early to mid 20th century. Additionally, pulp magazines were littered with unconventional ideals, morality and ideology which usually mirrored the protagonists. Lastly, we can see examples by looking at a sub-genre of the western which has been dubbed fondly as the spaghetti western. The spaghetti western was part of yet another film movement known more popularly as the revisionist western, which often times portrayed the lead character(s) sometimes as morally ambiguous. A characterization that made the great Clint Eastwood a household name to millions across the globe. Taking a closer look at Frank Miller’s work you will notice the similarities that have been borrowed that are then used to create a fresh and unique representation of the antihero.

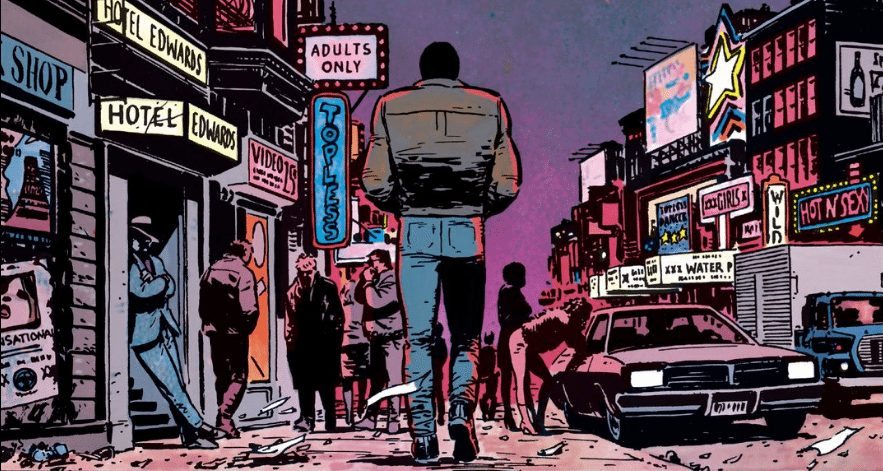

Antiheroism is not just about the protagonists but the very cities and settings that these narratives takes place. Take the city of Gotham and Sin City (or Basin City) and one can quickly find similarities. Firstly, Miller manages to embed an almost cynical-like motif to both cities. For example, the city is overrun with crime, the innocent and the weak are killed or mistreated and corrupt menacing figures overlord in positions of power. The city officials, including the police, are untrustworthy and blackmail is the cost of doing business. A compelling comparison of the two cities and their antiheroic nature takes the reader down an avenue of contradiction, intrigue and fortitude, which starts with their very redemption. Despite all of the moral attrition that has accumulated and the travesties that have plagued the city, both Gotham and Sin City are not too far gone; they can still grasp and crawl their way to redemption. In a sense the city is a mass representation of the very citizens that reside within her, two conflicted and opposing moral forces struggling. The good wrestling for the restitution of morality and the bad strangling mercilessly the very fibers that could strengthen and defend the city. Within Miller’s Year One and Sin City, the reader usually finds that the protagonists must take a hard look at the city and in the process they internalize the mirrored representation of their own ambiguous actions. They are then put in a position where they sift through the murky adulterated composition of good and bad and decide whether the city or individual (themselves included) validates redemption.

A common idiosyncrasy of the antihero narrative is the neurotic crushing pressure of insecurity. Many times we find Marv and Batman at a crossroads of self-reflection that sometimes cripples their efforts. Bruce Wayne in Batman: Year One dwells on his dead father’s potential disappointment because he has not yet enacted his plan for revenge. Bruce’s commentary during the final pages of the first chapter demonstrates that he must wrestle his own demons before he can accomplish a task that he has bestowed upon himself. In Sin City: Vol 1 we see Marv striving to overcome his own self imposed penance after Goldie is murdered right next to him. Not only does his insecurities drive him to seek revenge, he also believes that he owes Goldie for simply giving him attention. The intricacies of both Bruce’s and Marv’s insecurity is what creates a major component of their antihero psyche. Often times we find our ambiguous heroes question their abilities and weigh their sanity against reason. For example, Marv questions whether or not what he’s seeing or hearing is actually happening, his insecure nature and subconscious reminds him that he has not taken his medication. These comprehensive notions of insecurity and self-loathing can manifest into guilt, which then cripples their efforts. In some forms of literature the internal delphic struggle of the antihero usually can manifest into a second antagonist. The common saying “my own worst enemy”, rings true in the case of Batman and Marv.

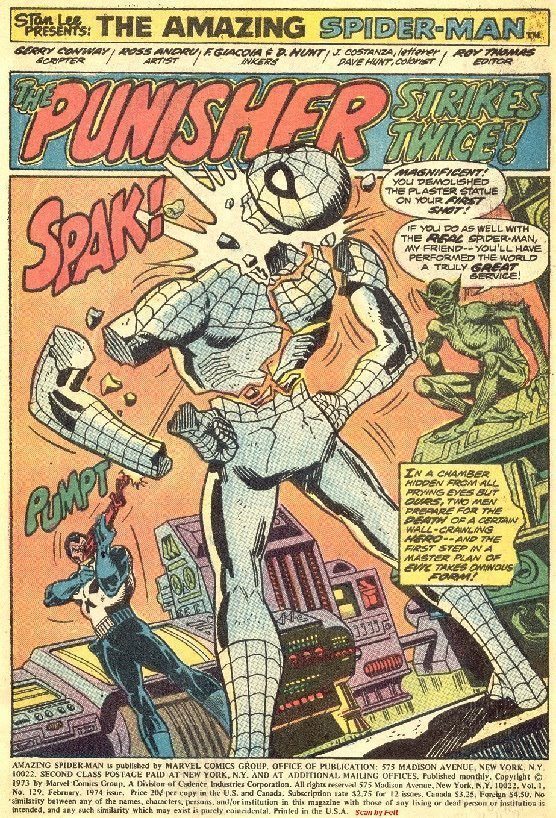

Revenge is another very common writing trope that is found within the antihero genre. The revenge genre has a long seedy past that can most notably be traced back to a more recent time in history. The revenge genre is a subgenre of the exploitation films of the 1970s. By definition the exploitation film describes itself, typically they were films which attempted to earn a profit by simply exploiting a current trend or a lurid subject. During the glory days of the exploitation era of filmmaking, it was very common to see a morally defunct character brazenly mete out justice with zero regard for law or safety. This particular brand of entertainment quickly led to ancillary avenues of entertainment that inevitably led many companies down a road of profit and prestige.

Ms. 45 – Director: Abel Ferrara (1981)

Comic book publishing companies were among the culprits to jump into the mix of the antihero narratives. The vigilante known as The Punisher had his debut in the 1970s and quickly became on everyone’s list of top reads. The thing about Frank Miller is that he doesn’t just play the same tune, he takes the antihero archetype and transforms it into something fresh, unique and complex. The complexities of Marv’s need for revenge is not just blind rage or anger, but an emotional response triggered by the basic of human need for human connection. By design his motives are fairly simplistic, however the simplicity is genuine and complex when paired with his very real psychological issues. Comparatively, when the reader takes a look at Batman in Year One, we see a man that is not quite in control of his emotions as he’d like to be. His need for revenge is strong but so is his desire for friendship and redemption. The complexities of Miller’s characters is what sets them apart from other less developed antiheroes.

As mentioned earlier, Frank Miller delves heavily into the film noir genre for inspirational characterizations. The writing styles of Sin City: Vol 1 and Batman: Year One are very similar in terms of theme and motif. They follow along the similar lines of the film noir film movement where we find a world filled with dark streets, rainy nights, down and out detectives (antihero), and the beautiful femme fatale. The femme fatale are just as important in Miller’s work as they are in the film movement of the early 20th century. Femme fatales are often used to ensnare the antihero, this common trope can propel elements of the plot that create suspense, distrust, confusion and sometimes serve as an introduction to societal taboos. An example of Miller’s flirtatious nature with the social taboos, can be seen when Marv sleeps with Goldie a hooker, and to some extent when Gordon cheats on his wife. A femme fatale is characterized often times as a seductive woman whose relentless aura ensnares men, often taking them down a path of danger and deadly situations. In Year One, Frank Miller uses his skill set to take the common archetype and manages to weave it into something similar but uniquely refreshing at the same time. An example of his prowess can be seen when the reader takes a closer look at the alternative narrative within Year One that pertains to Lieutenant Gordon. The femme fatale title in this instance goes to Gordon’s partner Sergeant Essen. Although Essen is not the typical fatale with a secret agenda of her own, she does however inadvertently create a situation that could easily have spun out of control. The adulterous affair that carries on between Gordon and Essen dragged Gordon down a dangerous path that left him vulnerable and open to attack by the very enemies that he aimed to take down. In Sin City: Vol 1 the femme fatale leads Marv down a dangerous path of revenge. This is another example of Miller’s twist on the femme fatale, even in death Goldie plays her part.

Clockwise from left: Rita Hayworth, Ava Gardner, Gene Tierney

The architectural rhythm behind Frank Miller’s antihero and the world he resides in is the staple of his creative career. The artistry of images fused with the narrative is what separates Miller’s work from the rest. Borrowing heavily from the expressionist film movement, that then catapulted the film noir genre, Miller’s chosen palette of colors (or lack of) is the defining stroke that makes his work brilliant and memorable. In many ways Miller uses artistic elements much like a film director or cinematographer would use to create mood and emotional subtext, each element adding more depth to the antihero’s journey. Patterns, shapes and the use of negative color space all used to add emotional layers to the protagonist. An example of color reversal or negative color space, is when Marv in Sin City climbs the city building’s wall and his image appears as a simple silhouette but his shadow is what defines the brick wall he climbs on. Miller is using this to prod the reader with the appropriate emotional responses, he’s guiding us through emotional subtext in hopes we can understand what his antihero is going through. The high contrast tones and use of shadows to define color space within the panels of Sin City is an ode to Miller’s fondness of the film noir genre. Although the pages of Year One does not share the dynamic depth that Sin City offers, it does however display color choices that guides the reader toward similar emotional responses. Another crucial setting for the antihero is the dreary but clever and sometimes colorful voice over of the protagonist. Often times, voice over in film is used as a form of exposition and to fill in key areas of the plot. By delving back into the pages of Sin City you will quickly notice how well the “voice overs” work in keeping the narrative moving forward. One contrast between Batman: Year One and Sin City: Vol 1 is the noticeably different narrative styles. In Year One, Miller opts for dual opposing narratives between Batman and Gordon, which works in tandem to create a unique approach to the usual antihero voiceover.

It’s not hard to see the influence that Frank Miller’s antiheroes have had on pop culture. Every single Batman film since 1989 has borrowed the dark themes of Year One. Sin City has spawned countless copycat crime sagas that have tried desperately to capture the kind of magic that Miller wields effortlessly within the panels of Sin City. The dark noir themes and the complexities of the antihero that we read in the pages of Batman: Year One and Sin City: Vol 1 is a testament to Miller’s supremacy within the arena of down and out detectives, crime fighters and not so bad criminals. In retrospect, you could say that Miller has defined contemporary antiheroism and has carved out a genre that is something entirely different and unique.

Written by Michael Flores

Works Cited

“Antihero.” Oxford Dictionaries.com. Oxford Dictionary, 2016.

Sat. 23 January 2016.

Miller, Frank. Batman: Year One. New York: Dark Horse, 1986. N. pag. Print.

Miller, Frank. Sin City. Vol. 1. New York: Dark Horse, 1991. N. pag. 7 vols. Print.